Our culture is built on a patriarchal foundation. The “great men” of the past, the leaders in philosophy, science, and religion, have been unable to see that the women around them—women they often claimed to love—could be their equals. Their brilliance and their blind-spots shaped our world.

Drawing from my current project on the idea of women’s equality, I want to spotlight four intellectual leaders who represent the failure of men to respond constructively to the rise of the idea of women’s equality in the critical period from the middle of the nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century.

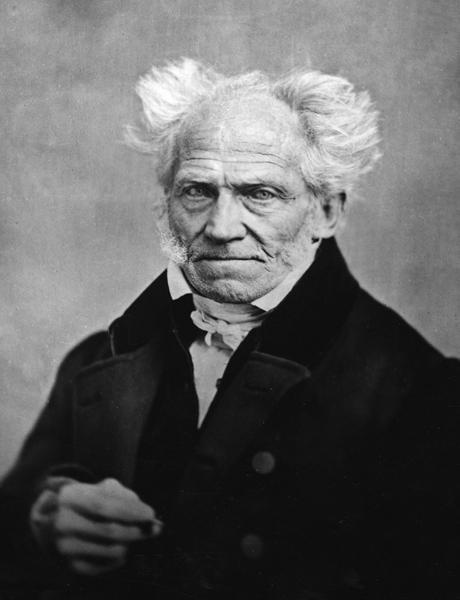

These four men—the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, the physician Charles Delucena Meigs, the economist Alfred Marshall, and the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer—are interesting because in each case there are strong reasons we would have expected them to have known better.

These men had a worldview or professional position that should have made them more likely to see the equality of women. Each contributed significantly to the moral evolution of humankind; but they were unable to use their critical faculties to see beyond their cultural constraints to appreciate the importance of gender equality.

The enduring failure of these and so many other men to appreciate the interests and equality of women is striking in light of what sociologists call the “contact hypothesis.” This theory, which is generally credited to the psychologist Gordon Allport, holds that conflict, prejudice, and misunderstanding can be reduced when groups are engaged in long-standing contact.

The strongest validation for contact theory has been the rapid change in attitudes towards the LGBTQ community over the past twenty years. There is a large literature showing that people who have had personal interactions with someone who is gay or lesbian are more likely to be open to normalizing same-sex relationships. Learning that a friend or relative identifies as LGBTQ is a particularly potent agent for attitude change.

Contact theory does not seem to have worked its magic for the acceptance of women as equals. Women and men have lived in close proximity as long as there have been men and women. Having mothers, daughters, wives, and sisters did not make men more sympathetic to the opportunities and aspirations of women.

As I discuss in this new book project, ours is a history of stupid brilliant men who could not see the truth about fifty percent of the people around them. This persistent inability to see the basic equality of the women with whom they interacted is what I call male pattern blindness. It is a remarkable and yet nearly universal dysfunction that has afflicted both the man in the street and the great men of philosophy, science, and religion from the earliest time until the present.

In the next few posts I will briefly profile four of these great men. First up: Arthur Schopenhauer, a philosopher of morality and misogyny.

Posts in this series on Male Pattern Blindness:

- Overview

- Arthur Schopenhauer, a philosopher of morality and misogyny

- Charles Meigs, a prominent physician for women and proponent of their subjugation

- Alfred Marshall, a rationalist economist who rationalized patriarchy

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a theologian for social justice and wifely subservience

- Some concluding thoughts

7 Pingbacks