My current project on the idea of women’s equality has led me to ponder why so many men who had both intellectual and circumstantial reasons to understand and endorse women’s equality failed to do so. I have been using this blog to briefly profile a few prominent examples of this male pattern blindness. My previous post highlighted the illustrious philosopher and infamous misogynist Arthur Schopenhauer. This time, I offer for your consideration the nineteenth century physician Charles Meigs (1792-1869).

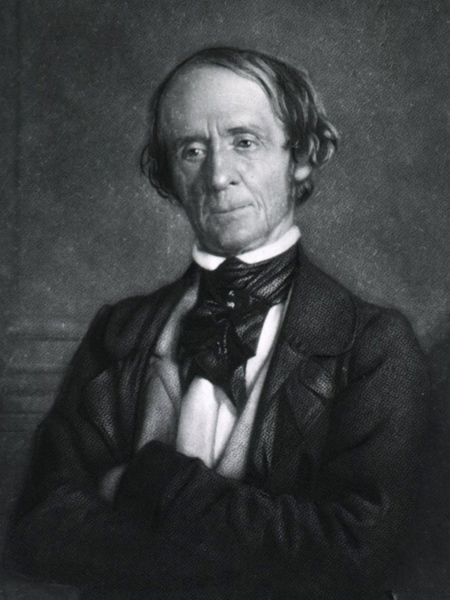

Dr. Meigs was a distinguished faculty member at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. In the middle of the nineteenth century he was widely considered the leading American specialist on women’s medicine and obstetrics.

A useful launching point for delving into the character of Dr. Meigs is the tragic death of pioneering feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft in September 1797. Wollstonecraft, then 38 years old, was one of countless women who suffered painful deaths in childbirth from puerperal sepsis, an infection of the genital tract. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were several theories about the causes of puerperal fever, most of which were categorized as what were then called “putrid miasmas” or “atmospherical influences.” Dr. Meigs described puerperal fever as “an unspeakable terror” and attributed it to bad air and bad luck.

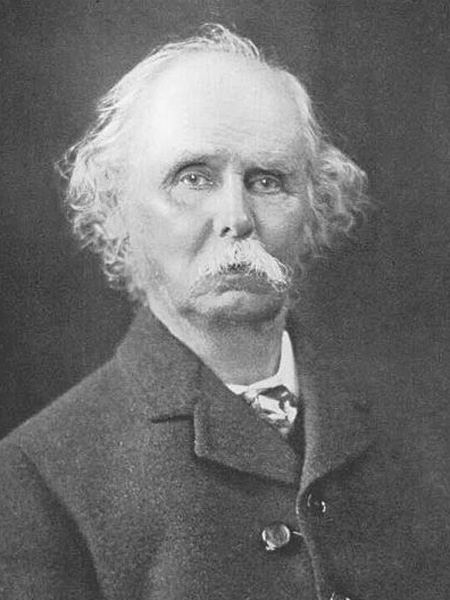

An alternative possibility was proposed by the physician and writer Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. (who was also, of course, the father of Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.). Early in his medical career, Holmes, Sr. published a paper advancing the argument that puerperal fever was infectious and was carried on the unwashed hands of midwives and obstetricians: “the physician and the disease entered hand in hand into the chamber of the unsuspecting patient.” Despite the strong evidence he marshalled, this thesis was surprisingly controversial.

The illustrious Dr. Meigs took the intimation that doctors were at fault for the death of so many women as a great affront. In his 1854 book, On the Nature, Signs, and Treatment of Childbed Fevers, he criticized Holmes’s contagion theory as “nonsense.” Meigs offered a chilling description of his own practice: “I have proved it in my own case, over and over again, since I have gone from the houses of persons laboring under the most malignant forms of the disease, and from participating in necroscopic examinations, without carrying the malady with me.” Meigs expressed his confidence that doctors were gentlemen, and “a gentleman’s hands are clean.”

The same stubborn arrogance that contributed to Dr. Meigs’s error on puerperal fever also made him a lifelong opponent of anesthesia. Meigs was concerned about the risks of this relatively new technology, but he also argued that pain was a natural and appropriate part of childbirth. Labor-pain, Meigs wrote, is “a most desirable, salutary, and conservative manifestation of life force.”

(William Foster, 1891)

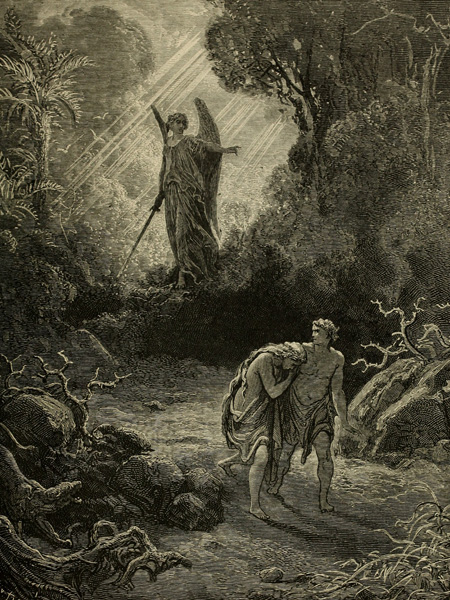

Meigs connected his acceptance of painful labor to the biblical decree that suffering in childbirth would be the punishment for Eve’s original sin. He warned against the “doubtful nature of any process that the physicians set up to contravene the operations of those natural and physiological forces that the Divinity has ordained us to enjoy or to suffer.”

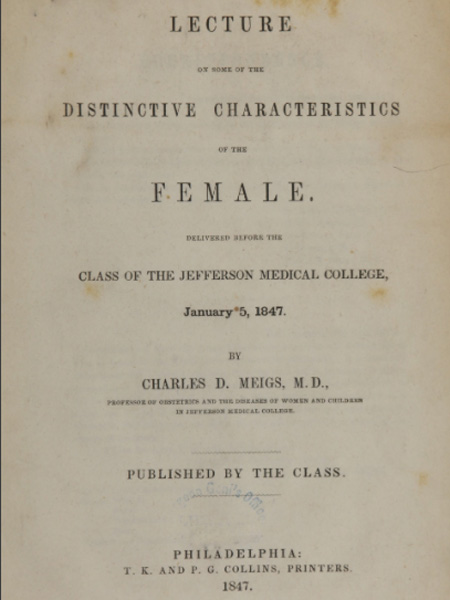

In addition to his callous endorsement of women’s pain, Meigs expressed the soft misogyny of putting women on a pedestal. In a medical school lecture on “Some Distinctive Characteristics of the Female,” he warned that without the influence of women, society would relapse into “the violence and chaos of the earliest barbarism…. It is not until she comes to sit beside him… that man ceases to be barbarous.”

The connection between Meigs’s caricature of women on a pedestal and their subjugation was made clear in the same medical school lecture. Surrounded by his eager male students, Dr. Meigs shared his deep insights into the female character: “she has a head almost too small for intellect but just big enough for love.” His description of woman’s “intellectual nature” follows along this line:

She has nowhere been admitted to the political rights, franchises, and powers that man arrogates to men alone…The great administrative faculties are not hers. She plans no sublime campaigns, leads no armies to battle, nor fleets to victory. The Forum is no theatre for her silver voice, full of tenderness and sensibility. She discerns not the courses of the planets. Orion with his belt, and Arcturus with his suns are naught to her but pretty baubles set up in the sky.

C. D. Meigs, “Some Distinctive Characterstics of the FEmale” (1847)

Dr. Meigs surely knew women whose intellect and character could have disabused him of this prejudice. On the subject of “pretty baubles in the sky,” for example, he could have turned to Hannah Bouvier, a fellow member of the small and insular “Old Philadelphia” elite. Bouvier was a popular science writer and the author of a leading astronomy textbook.

And, of course, there was Meigs’s wife, Mary, who was described as having “great intellectual powers and common sense, with a strong love of justice.” The Meigses began their life together in Georgia, where his father was the first president of the University of Georgia. After two years in the South, however, Mary was revolted by slavery and had the fortitude to insist that they move to Philadelphia.

Charles Meigs dedicated his life and his science to the health of women. That is an admirable thing, to be sure. Nonetheless, his experience and expertise failed to open his eyes to the equality of women. Dr. Meigs was a man who should have known better, but didn’t.

Moral: A scientific disposition is a weak competitor to cultural hegemony and pig-headed stubbornness.

Next up: Alfred Marshall—a social scientist who urged economics to turn toward social welfare, but turned away from the brilliant woman standing next to him.

Previous Profile: Arthur Schopenhauer, a philosopher of morality and misogyny.

The Overview: Male Pattern Blindness

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

5 Pingbacks