As a spin-off from my current project on the idea of women’s equality, I have been profiling four men whose circumstances and smarts should have led them to see the equality of women—but didn’t. This is what I call male pattern blindness. It is the inability of otherwise incisive men to see and appreciate that women are equal to men.

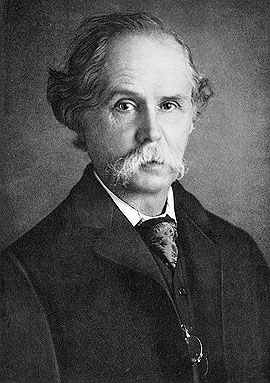

Next on the list is the great British economist Alfred Marshall (1842-1924). Marshall was the founder of neoclassical economics and deserves particular credit for insisting that economics should be concerned with social welfare rather than just wealth.

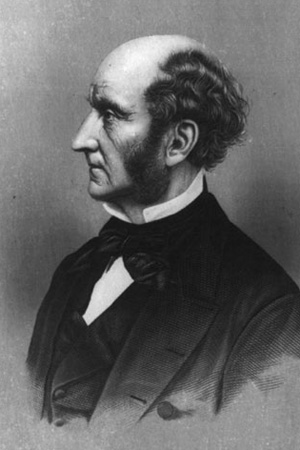

Marshall would have first learned his economics from John Stuart Mill’s Principles of Political Economy (1848), which served as the foundational economics text of the time, before being supplanted by Marshall’s own Principles of Economics (1890).

Mill’s 1869 book, The Subjection of Women, singled him out as one of the earliest male philosophers to appreciate and promote the equality of women. As with the women of the early suffrage movement, Mill was particularly critical of laws that essentially stripped married women of the right to own property. The principle of coverture—which, by the way, wasn’t fully rejected by the US Supreme Court until 1966—held that the legal identity of females was “covered” first by their fathers and then their husbands, who gained sole control over their income and property upon marriage. Mill saw coverture as so onerous that he expected that if equality gave women any other opportunity for financial security, they would reject marriage altogether.

Marshall shared Mill’s view that women’s equality threatened the institution of marriage. But, where Mill was concerned about its disadvantages for women, Marshall came to believe that it was men who would lose interest in marriage if they couldn’t be in charge:

[Marriage is] a sacrifice of masculine freedom, and would only be tolerated by male creatures so long as it meant the devotion, body and soul, of the female to the male. Hence the woman must not develop her faculties in a way unpleasant to the man.

This was not always Marshall’s perspective. He was more open-minded in 1877 when he married his former student Mary Paley.

At the beginning of his career, Marshall had served on the committee promoting informal lectures for women at Cambridge. He owned a first edition of Mill’s The Subjection of Women, and expressed agreement with Mill that “marriage should be an equal condition … an equal contract.” On a trip to America in 1875, he wrote his mother with enthusiasm about the liberal Unitarian marriage vows he encountered there. Marshall and Paley wanted to omit the standard vow of obedience in their marriage ceremony. Paley’s father, who officiated, refused to abide this modernism and insisted on the traditional vows. In the way of economists, Marshall and Paley entered into a side-agreement contracting out of that clause.

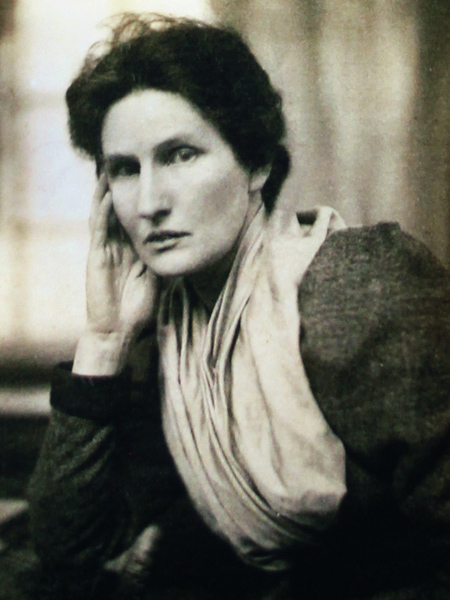

Mary Paley was one of those exceptional women who should have made the fact of women’s equality obvious to all who knew her. She was one of the first women to attend Cambridge University as part of the small inaugural class of the Newnham College for women.

[Cmglee, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons]

Even with their own college, the status of women at Cambridge remained decidedly second-class. Lectures and exams for women were set informally, and women were not awarded degrees. Still, on the strength of her performance there, Paley was appointed as Cambridge’s first female lecturer in economics, though limited to working with female students.

Then, Mary Paley married Alfred Marshall.

Interestingly, it wasn’t just women who couldn’t hold full academic appointments. Married men were also barred from teaching at Oxford and Cambridge.

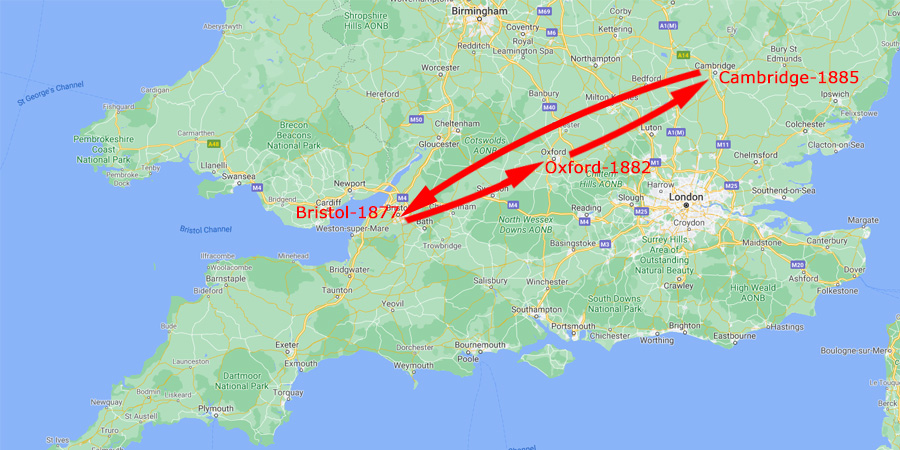

Alfred Marshall was sufficiently committed to Mary Paley to give up his Cambridge post for her. They moved to Bristol, where a new college was being built with the goal of educating working men and women. It was the first British college to admit women on an equal basis and was not subject to the marriage prohibition. Alfred Marshall became its first principal. He pushed for a lectureship for Mary Paley as well. This was agreed to, but with the onerous condition that her salary be deducted from his. Paley was a popular lecturer for women and men in mixed classes at Bristol.

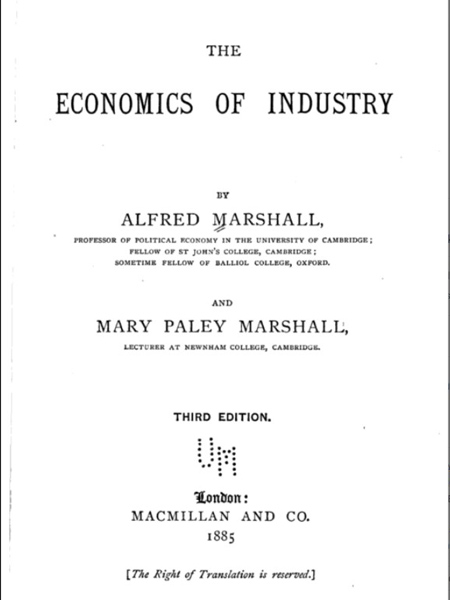

Marshall’s reputation was established with his 1879 book, The Economics of Industry. Mary Paley was credited as the coauthor, but in actuality it had originally been her project from before they were married. The quality of the writing and the book’s accessibility contrasts with Marshall’s other books, a difference that is usually attributed to Mary Paley.

In 1882, the rules changed to allow married faculty at Oxford and Cambridge. Marshall and Paley were both hired at Oxford, though she was again limited to teaching female students. Three years later, they were invited back to Cambridge. Alfred Marshall took up a prestigious professorship in political economy. Mary Paley returned to teaching the women of Newnham College.

In his inaugural Cambridge address, Marshall expressed his desire to use economics to deal with human suffering and “to discover how far it is possible to open up to all the material means of a refined and noble life.” Nonetheless, Marshall’s attitude towards women was shifting. His concern for human well-being did not incorporate women’s equality.

Indeed, Marshall became one of the leading opponents of giving women equal status at Cambridge. As the chair of the economics faculty, he vigorously fought every initiative for women’s advancement and joined the vocal majority of Cambridge alumni in strongly opposing granting degrees to women. He lobbied fiercely against giving regular lectureships to women, arguing that lecturing to largely male audiences was inappropriate for women, and could damage their character.

Other leading economists recognized Mary Paley as brilliant and capable. John Maynard Keynes, who knew both Marshall and Paley well, puzzled over the change in Marshall’s outlook:

In spite of his early sympathies and what he was gaining all the time from his wife’s discernment of mind, Marshall came increasingly to the conclusion that there was nothing useful to be made of women’s intellects.

Cambridge economist Austin Robinson described Paley’s life as “forty years of self denying servitude to Alfred.” Why, Robinson wondered, did he “make a slave of this great woman and not a colleague?”

The eminent Cambridge historian George Macauley Trevelyan notes that “Neither in Alfred’s lifetime nor afterwards did she ever ask, or expect, anything for herself. It was always in the forefront of her thought that she must not be a trouble to anyone.” We are left to wonder how economics might have advanced had Paley decided to be a trouble.

Alfred Marshall was an innovative thinker who was committed to addressing the social problems of the day. He knew the arguments for gender equality in Mill’s The Subjection of Women and professed support for equality at the time of his marriage to Mary Paley. He then spent forty-seven years living with a woman who had proven her intellectual abilities in direct comparison to men. And yet, he reverted to the prejudices of his era. Marshall was a man who should have known better, but didn’t.

Moral: Rationalists will have their rationalizations.

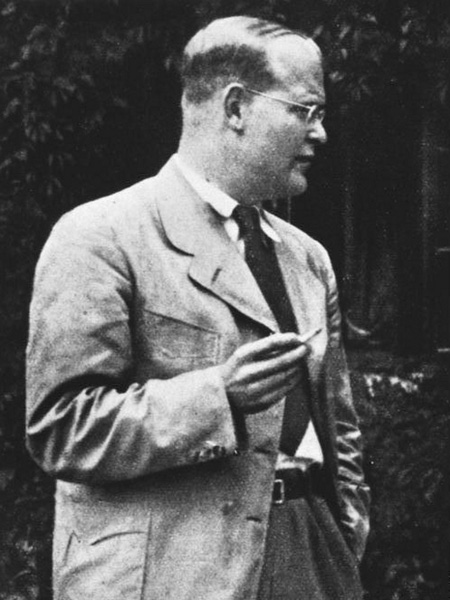

[ Bundesarchiv, Bild

CC BY-SA 3.0 de]

Next up: Dietrich Bonhoeffer—a beloved theologian and martyr for social justice who wouldn’t accept women’s equality.

Previous Profiles: Arthur Schopenhauer, a giant of moral philosophy and misogynist prejudice, and Charles Meigs, a prominent physician and pillar of patriarchy.

The Overview: Male Pattern Blindness

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

3 Pingbacks