(Anselm Feuerbach, 1869)

Love is a sublime, but complicated, part of life. Here, though, is a secret about love that ought to be straightforward: It has always been known that authentic love requires seeing the interests of another as your own. The Buddha emphasized love focused on the good of others. Aristotle described love as one soul in two bodies. Jesus and Muhammad called on us to love our neighbors as ourselves. The German philosopher Georg Hegel wrote that “Love means in general the consciousness of my unity with another.”

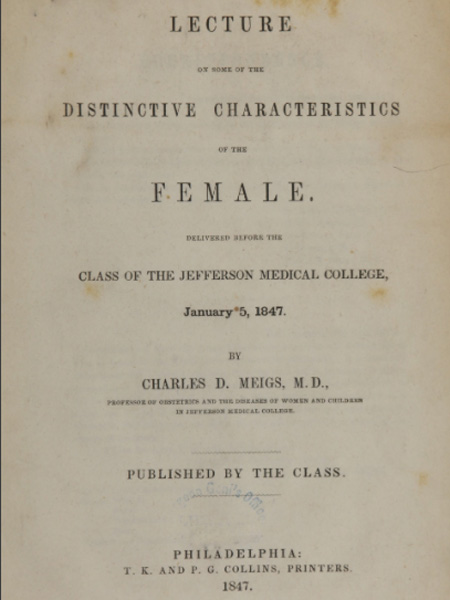

Consider, then, what Hegel had to say about women. In his Philosophy of Right, just after emphasizing unity as the essence of love, he shared this bit of patronizing profundity:

Women may well be educated, but their minds are not made for the higher sciences, for philosophy, and certain artistic products which require a universal element. Women may have insights, taste, and delicacy, but they do not possess the ideal. The difference between man and woman is the difference between animal and plant.

Hegel, Philosophy of Right, (1820) para 166

Um, Georg, how is love as “unity” supposed to work under those conditions?

If authentic love between adults requires identifying with another person and taking their interests as your own, it must also require seeing the other as an equal. If their interests are just as important as yours, you must accept them on the same level, with the same standing and agency.

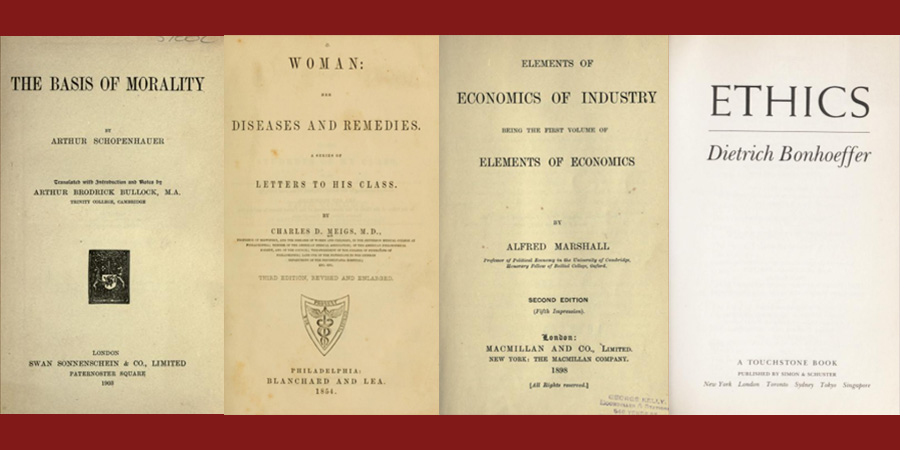

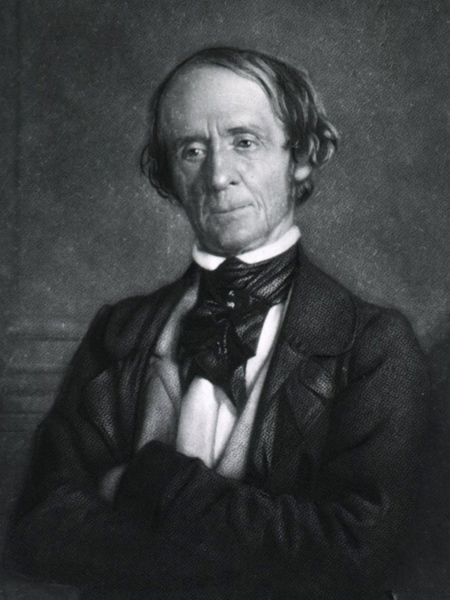

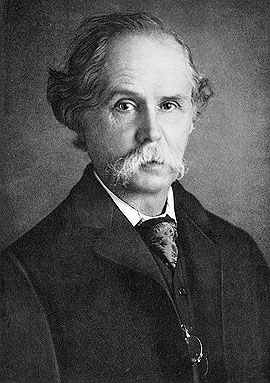

For most of history, however, our great (male) thinkers have insisted that women are inferior to men. Aristotle, the first person credited with the systematic study of biology, thought women were “misbegotten males,” the result of some procreative defect. He said you could tell women were inferior by the sound of their voices. After more than two-thousand years of thinking it over, the state of the art had advanced only so far as nineteenth-century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer’s confident assertion that you could tell women were inferior by the shape of their bodies.

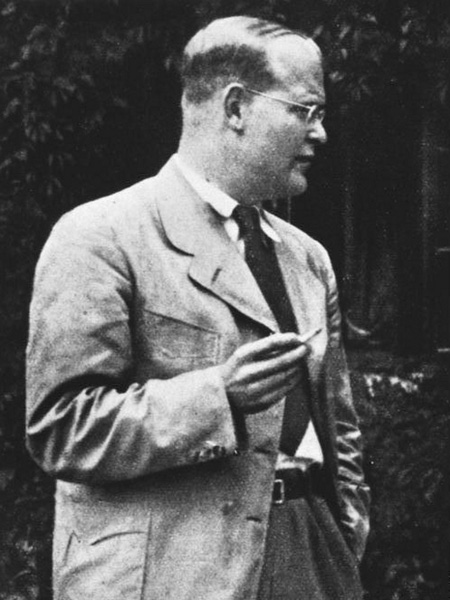

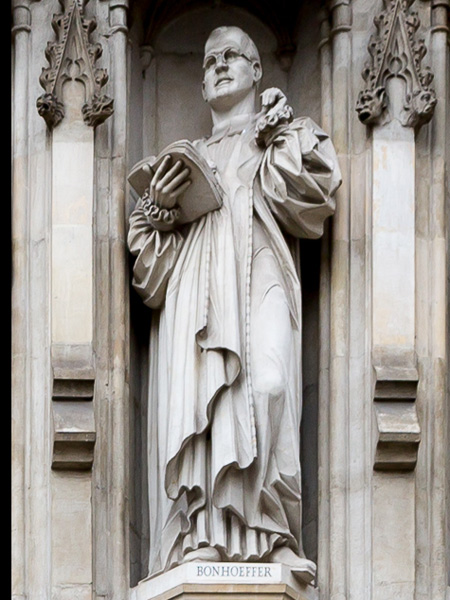

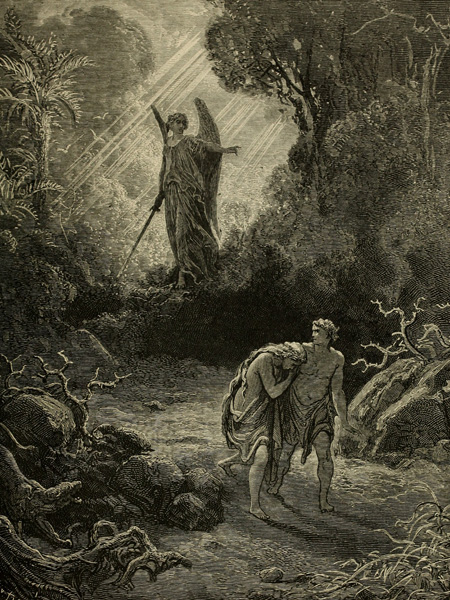

The theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer comes about as close to sainthood as Protestants allow. He is known for his resistance to Nazism and for his argument that ethics requires learning to see “the view from below.” He challenges us to overcome the ways power and privilege distort our understanding of what it means to care for others. Nonetheless, he called it a “rule of life” established by God that “the wife is to be subject to her husband,” and criticized marital equality as “modern and unbiblical.”

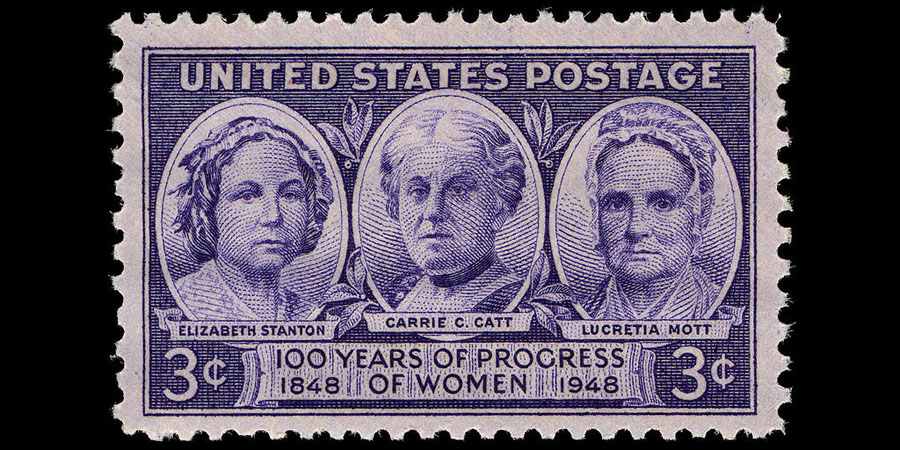

Bonhoeffer was surely right that women’s equality is a thoroughly modern idea. Apart from a few lonely voices, there was no organized movement for women’s equality before the nineteenth century. A full-spectrum effort for equality in the home and workplace only began to gain traction in the 1970s.

If equality is required for authentic adult love, that means that throughout history such a love was not a real option for most people. Even today, in much of the world the equality of women is more an aspiration than a reality. Authentic love between men and women remains beyond the reach of those constrained by persistently patriarchal institutions and cultures.

Given this reality, it is noteworthy that the one place love has been less encumbered by patriarchy and paternalism, even if not by other prejudices, is in same-sex relationships. Indeed, the Athenian philosophers better understood love in the context of male friendships than in relationships between men and women. Aristotle saw the pinnacle of human connection in the mutual caring between men of equal status and power.

On Valentine’s Day, let’s appreciate that the rising, if still imperfect, acceptance of women’s equality makes the possibility of authentic love between men and women widely possible for the first time in history.

The secret to authentic love has been known forever. But understanding this “secret” and giving men and women the potential to experience authentic love with each other is something new. Our world is built on thousands of years of thought and practice that rejected the equality of women. If we aspire to a world of authentic love, we must continue the hard work of personal and social change to make that possible. This means grappling with everything from who does the dishes to who serves in Congress. It particularly depends on changing the attitudes and behaviors of men.

Valentine’s Day is a fine occasion for cards and flowers, but now the secret is out. If true love is the goal, we must commit to the equality that is its essential foundation.

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better:

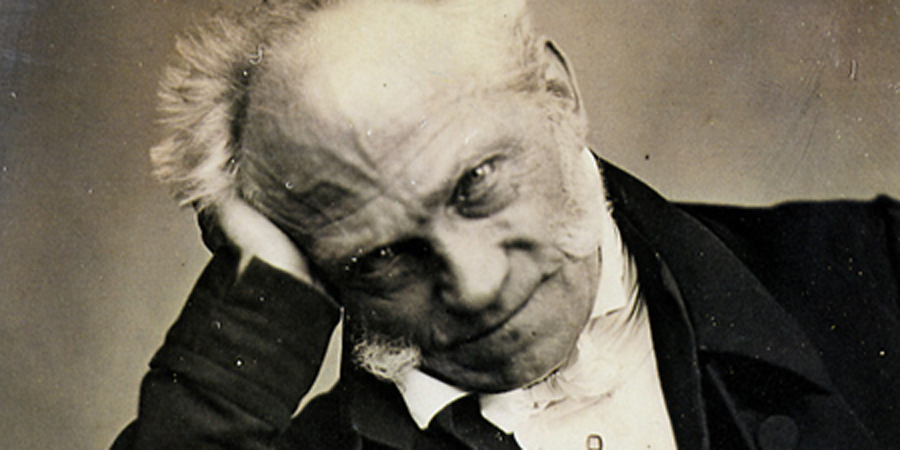

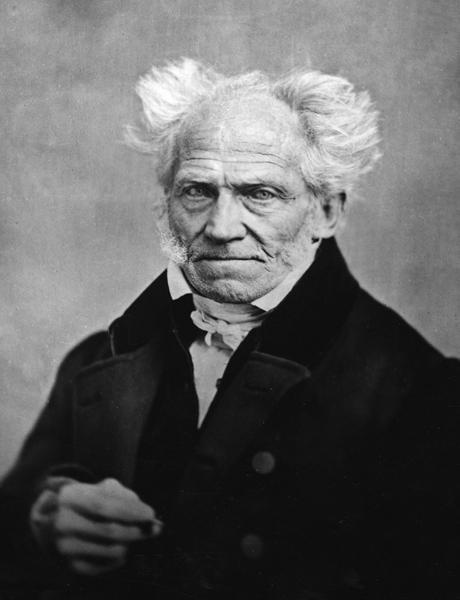

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better: Arthur Schopenhauer

Four Men Who Should Have Known Better: Arthur Schopenhauer