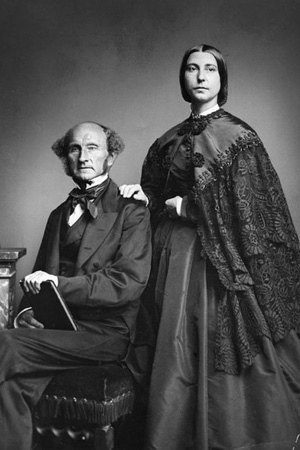

In 1851, American women’s right activist Lucretia Mott wrote to William Lloyd Garrison and Helen Benson Garrison describing a visit from an English businessman, Herbert Taylor. Herbert Taylor was a son of Harriet Taylor, who had just married the philosopher John Stuart Mill. Herbert Taylor gave Mott a copy of a new essay from the Westminster Review on “The Enfranchisement of Women.” Though published without citing an author, the essay was generally attributed to John Stuart Mill. But, Mott shared a story from Herbert Taylor that Harriet Taylor said John Stuart wrote the essay and John Stuart said that Harriet Taylor wrote the essay. This story encapsulates a long-standing puzzle about Harriet Taylor Mill’s intellectual influence on John Stuart Mill.

In the almost exclusively male world of traditional political philosophy, John Stuart Mill stands out as one of the great exceptions—a major figure who recognized the injustice of women’s inequality. Mill’s 1869 The Subjection of Women is a critical landmark on philosophy’s slow path towards enlightenment on this issue.

Without taking away from the importance of Mill’s contributions, there are a few points worth noting. First, of course, is that there are a number of women who had already gotten there, including most famously Mary Wollstonecraft in her Vindication of the Rights of Women [1792]. (And, even on the male side, I would highlight Condorcet’s On the Admission of Women to the Rights of Citizenship [1790].)

A second point is that outside the Great Philosophers Club, women’s rights activists had already brought significant attention to this issue. The Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments, after all, came in 1848, twenty years before Mill’s book. The 1851 essay on “The Enfranchisement of Women” makes this preeminence clear:

[T]here has arisen in the United States, and in the most enlightened and civilized portion of them, an organized agitation on a new question–new, not to thinkers, nor to any one by whom the principles of free and popular government are felt as well as acknowledged, but new, and even unheard of, as a subject for public meetings and practical political action. This question is, the enfranchisement of women; their admission, in law and in fact, to equality in all rights, political, civil and social, with the male citizens of the community.

This brings us to the the third and central point about John Stuart Mill’s breakthrough views on women’s equality, which is precisely his personal and intellectual dependence on Harriet Taylor.

The mystery of who was really responsible for the 1851 essay highlights this larger question. My former colleague, Dale Miller has an excellent essay on Harriet Taylor Mill addressing this subject in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. But here is a shortcut for thinking about the provenance of the original essay: In The Subjection of Women, John Stuart Mill endorses a gendered division of household and remunerative employment (both from tradition and a fear that there wouldn’t be enough jobs to go around). The essay on enfranchisement, on the other hand, echoes the Declaration of Seneca Falls in insisting that allowing women to become wage earners is essential for true equality.

I think that difference highlights the importance and impact of bringing a woman’s standpoint to philosophy, and is sufficient for attributing the essay on “The Enfranchisement of Women” primarily to Harriet Taylor Mill.