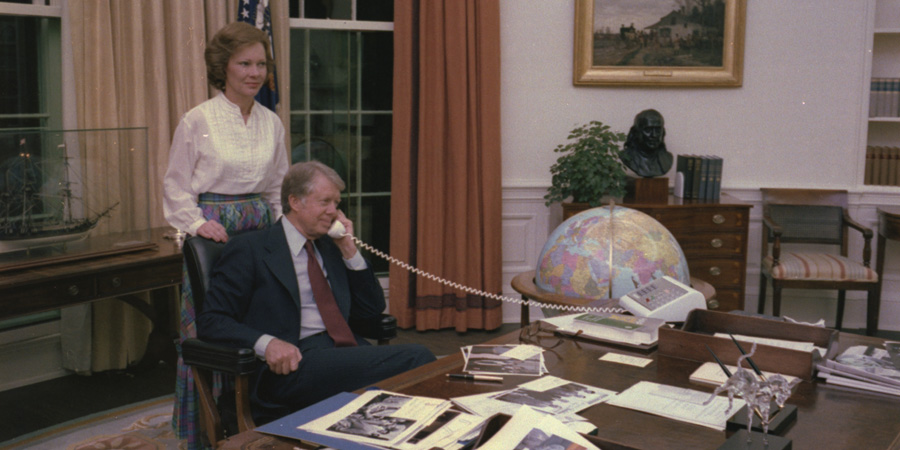

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter are celebrating their 75th anniversary this week to much well-deserved fanfare. Kevin Sullivan and Mary Jordan have a very nice Washington Post article about their relationship.

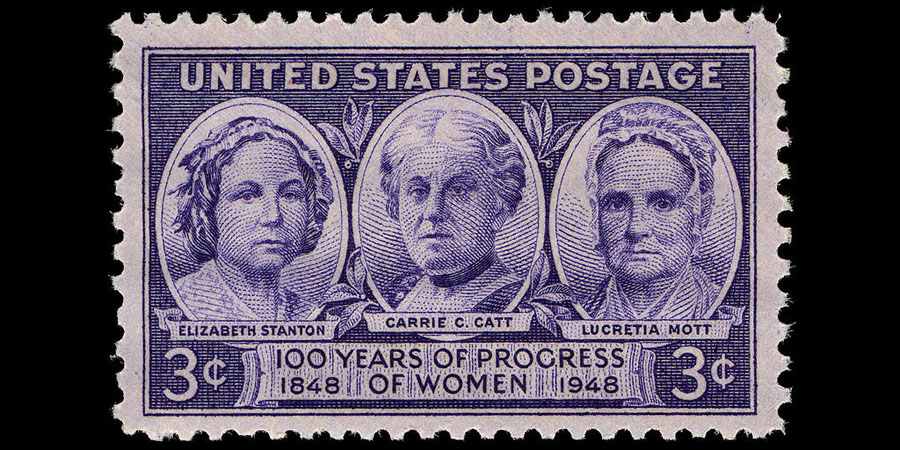

I have been writing a bit about some of the great men of the past who by dint of their positions and principles should have understood the urgent importance of women’s equality, but didn’t.

The Carters’ story captures some of the monumental changes in women’s equality over the past 75 years:

The Carters’ union has evolved with the times, starting as a traditional “father-knows-best” marriage in the 1940s and ’50s and eventually becoming a full partnership.

Jimmy Carter writes that in the early years of their marriage he “never considered it necessary to seek Rosalynn’s advice or approval.” He began his political career running for the Georgia Senate in 1962 without even telling her he had decided to do so.

Things came to a head in 1966, when he was running for governor, and she made it clear that she was not to be treated as an aide or servant. This marked a significant moment of enlightenment and a turning point for Jimmy Carter. After that he insists that their business, personal, and political lives were “shared on a relatively equal basis.”

The degree to which Jimmy appreciated Rosalynn as an equal is difficult to assess from the outside. Clearly, his career took a certain priority in their lives. And they were still swimming against strong cultural tides.

Jimmy Carter did become a strong advocate for gender equality. As president, he signed the 1978 bill sending the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the states for ratification.

Mary Clark argues in the Yale Journal of Law and Feminism that “Carter’s presidency marked a transformative moment in women’s appointments to the federal bench.” At the time he took office, only eight women had ever been appointed to the federal judiciary. During his four year term he appointed 41 female judges, including Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s appointment to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Rosalynn Carter was a strong political partner and advisor for her husband. She significantly enhanced the office of the First Lady. “She organized it and expanded it in ways previous First Ladies had either never imagined or never attempted.”

Two concluding points for this reflection. First, it remains an interesting question of what led Jimmy Carter to make this shift in perspective when so many other men of his generation could not do so.

Second, let’s note that while their son, Chip, said that Rosalynn “was a much better politician” than Jimmy, it was Jimmy who ran for governor and president rather than the other way around.